Data driven journalism (DDJ) is about analyzing databases of public interest and transforming them into compelling and engaging stories that include infographics, interactive data visualization, videos, news apps, games or any other multimedia resources.

The goal is to enable people be informed in a deeper way, to learn and gain knowledge based on figures.

DDJ is a powerful tool to protect the public interest. It enhances investigative journalism for unveiling corruption or any inequality that can hide behind the systems of education, health or justice.

How do we make these stories?

By analyzing data in the best possible way, using statistical methods, algorithms, or data mining models. We also use traditional techniques of investigative journalism.

The whole process should it be done with rigor and accuracy, verifying the data as any other source. We need to ensure the precision and trustworthiness of data that will be presented (as a fact) to our readership.

On this regard, if you are starting in DDJ, keep this advice in mind:

“Just as we are trying to avoid putting stories out there based on anecdotal evidence with no analysis, we’d like to also avoid publishing stories based on analysis in a vacuum”, says Robert Gabeloff, data journalist at The New York Times.

Data Journalism must to emphasize the human side of the story. We must go out to study how the data behaves in the real world.

Getting the best stories from people is mandatory to understand the context behind those datasets you are giving your faith. Without it, your story would be a cold and empty echo.

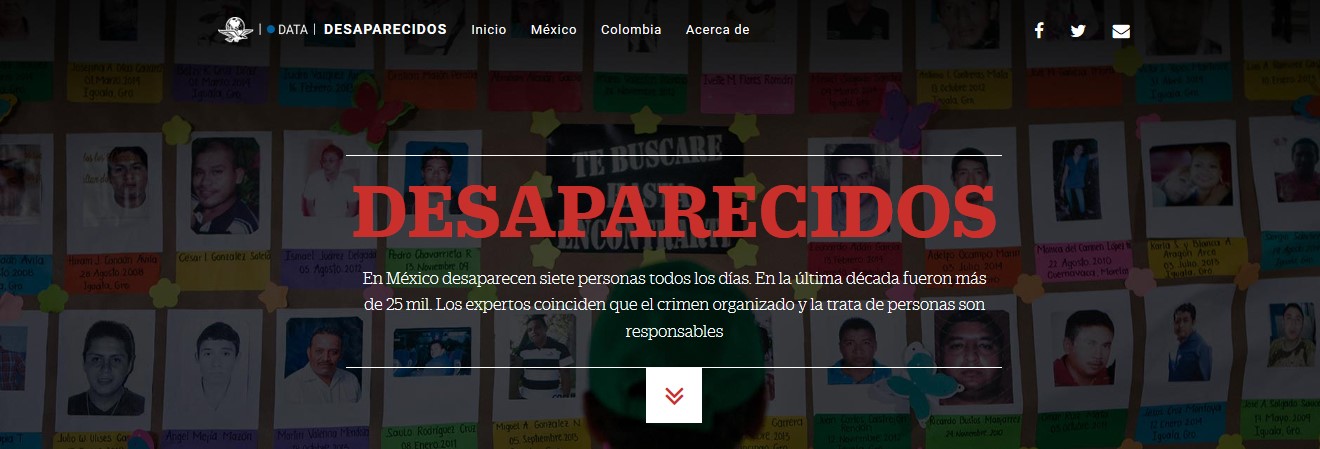

A recent example of the relevance of human face of data in journalism is Desaparecidos (Missing), a project done by diaries Universal México and El Tiempo Colombia.

Missing reveals the alarming number of missing persons in both countries because of violence, but puts them faces, names, the voice of relatives who cry out for justice . The project won, in April 2016, The Ortega y Gasset award for the best multimedia work.

Data, coffee and people

In 2013, I was investigating the recycling practices of households in the 81 regions of Costa Rica and how local governments supported these efforts.

The data analysis led me to Dota, a region of the province of San Jose, as the leader of mass recycling in Costa Rica.

In 8 out of 10 of Dota´s houses, paper, plastic, glass, and aluminum are separated from the common garbage. No other county in the country have such high percentages. Why?

To discover the answer, and the core of this story, was necessary to go there and conduct several interviews to find that coffee plantations were the main reason that explained the phenomenon.

In Dota, coffee constitutes a family business, from which most of the 1,900 homes of the county live, directly or indirectly.

The 90% of those families are part of Coopedota, a coffee cooperative renowned in the world for producing award-winning beans and for being the world’s first carbon neutral coffee producer (2011).

“If we are carbon-neutral, with sustainable practices in the business and the coffee plantations, it is logical that these reflect in the homes of our members,” commented to me Roberto Mata, manager of the cooperative.

To achieve those environmental practices, in 2008, Coopedota and the municipality launched a recycling program, teaching how to recycle in every home.

Because of the mass recycling, in 2012, the coffee producers of Coopedota received a half million-dollar prize for producing a bean in harmony with the environment. The international markets paid them $10 more per each one of the 50,000 quintals produced in 2012.

How would it have been possible to obtain this context to enrich my data story without doing the invaluable reporting on street?

That is why in my 10 DDJ commandments, number 7 is: “You shall not commit the mistake of avoid reporting. The data are not sacred. Between the data base and the story there always has to be Journalism”

To read the whole Dota´story in english, download it here.

Remember: we do not write stories or create data visualizations for other journalists, scientists, economists, sociologists, engineers, or data miners just for the sake of proving how good we are with numbers and their analysis.

Data journalism is for people and needs to be useful as meaningful.

One last thing:

Data journalists do not write stories as if they are putting together dense bricks of numbers and information. No, we are information architects and as good architects, we align the logic and the accuracy of data analysis in harmony with good content, writing and appropriate visual display.