Do you know what databases and algorithms are? Probably your answer is affirmative. If you have access to an Internet connection, both concepts will not be alien to your everyday life.

At least you may have a notion about what they are, how they work, and what they allow you to do. It is not uncommon to find information on this regard, such as this article by The Economist, which, in May 2017, explained why «The most valuable resource in the world is no longer oil, but data.»

You may know that some of the data that we generate from our devices connected to the web are massively collected and that they are «gold» for companies such as Netflix, Facebook, Google, Amazon, Apple and others, which analyze them to better understand our tastes and consumption patterns.

You may also know that there is a great debate about the way in which this power to control so much information at the global level should be regulated.

The use of databases and algorithms is not – and should not be – the exclusive domain for the businesses of Internet giants or for those who have the human and technological resources to exploit them.

In the last five years, the use of databases and algorithms has also spread among citizens and organizations, mainly those that promote the massive opening of information of public interest (open data) for a more transparent analysis and dissemination of the management of the State and governments of the world.

In Journalism, what is the use of databases and algorithms? Why is it important for journalists to learn to understand and use them?

Because the «superpowers» that journalists need to investigate more and better the power in the world basically rest in that duo.

A few months ago, during a conference at the Alberto Hurtado University in Santiago de Chile, I exemplified how data is present everywhere and how it can become an input to enhance the possibilities of journalistic investigation.

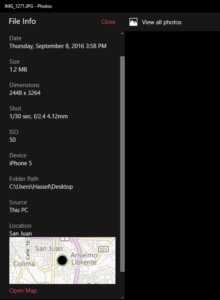

I showed this picture

I said that I had taken it at the Tocumen airport, in Panama, on October 17, 2016.

«While I was waiting to board the plane that would bring me to Santiago, I did what I always do: get a latte,» I told the audience.

After a few seconds of silence, I asked the attendees – most of them future colleagues – how many believed in the veracity of that story, why would they take it for granted, and if they trusted the source.

In the face of silence and doubt, I proposed the audience to do the right thing in good journalism: verify my statement, assess the evidence offered by the metadata that contained the picture in question.

What is metadata? you may ask yourselves. It is what the naked eye cannot see, but describes the information and the content behind the data.

To understand it better, I show you what was «hidden» (metadata) from the image of the mysterious cup of coffee.

As you can see, metadata in this image says more than what was visible to the naked eye, starting with the date. The photo had been taken a month and a half before the day of the flight to the Chilean capital.

In addition, it included the geographical location, which showed that the picture was taken in San Jose, Costa Rica, in the La Nación cafeteria, -where I work -, not at the Panama airport.

Before giving the outright false verdict, I reminded my future colleagues that we call ourselves journalists because we must always report, go out in the street. Data is a complement to that report.

In my statement, there was a second «lie» that metadata could not unveil. I had said that, on the way to Chile, I made a stopover in Panama.

The truth of this could only be confirmed by requesting a copy of my flight itinerary and interviewing the administrative coordinator of the University, who, without a doubt, would say that I did not stop in Panama, but in Lima, Peru.

That is to say, the traditional investigation methods continue -and will continue to be- fundamental in journalism.

The era of mass data and journalism

The case of this picture is just one example of the immense amount of data that humans and our machines generate every second and are susceptible to analysis.

Last year alone, the amount of information that circulated through the network reached the following figure:

1,2 zettabytes or 1,200,000,000,000,000,000,000 bytes

A byte is the minimum unit of information storage, enough to encode a number or a letter.

Although 1.2 zettabytes of information traffic through the web seems an unimaginable figure, in five years it will triple (3.3 zettabytes), primarily due to the consumption of video on mobile devices, according to a report by the Cisco Company.

We live in a time where the volume of data available on the Internet grows exponentially every day and its storage constantly becomes cheaper, which has favored the development of big data and the consolidation of data scientists.

What is Big Data?

In a very general definition, big data is the massive storage of data. It is logical to ask: What is the approximate volume of data needed to say that something is big data?

The answer is relative. It depends on the purpose of each person and on whether the size of the data is part of the problem. For some, processing 1,000 gigabytes of information is not an issue, for others, processing a gigabyte could be.

Now, Big data by itself is meaningless if data is stored without a purpose and, consequently, it is believed that the volume to be administered must always be exorbitant.

Storing information makes sense only if it is analyzed with the relevant techniques to infer from it behavior patterns of people or machines or if it allows us to make predictions about their future behavior.

The objective is simple: extract information and knowledge from data to make decisions.

«For me, big data is a minor term, data science is the important one. Big data is data accumulation; data science is what gives value to data. This is where the explanatory power of social sciences takes on its true value,» affirms Michael Herradora, the Costa Rican data scientist.

What is an algorithm?

Throughout this chain of data analysis, algorithms play a vital role.

An algorithm is a series of logical and ordered steps that allow finding the solution to a problem.

Engineers, for instance, analyze the problem, design a solution step by step, and execute the code on the data in question.

There are data mining or data extraction algorithms on the internet; there are algorithms that learn from the information that you leave and with it, they predict, with a certain degree of confidence, whether you would like such a movie or not, just to mention an example.

I am telling you all this with one purpose: to understand that, like it or not, data is everywhere and someone is always analyzing it. It is being used to do business – legal and illegal – and also to exercise a questionable surveillance over humanity.

Back in the Middle Ages, people talked of a theocentric society; God was the center of humanity. In the Renaissance, the center of humanity was man, his own creation and thought. Nowadays, it could be said that the center of humanity is heading towards the data that it generates. And this, obviously, is for its own good or evil.

SOS, I’m a journalist and I have a database

And, how is all this thing of databases, analysis and research linked to journalism?

We, journalists, should develop the same intellectual and technological muscle that exists in companies and in certain governments to collect and analyze data, to apply it for the good of society, of course.

Not developing those skills to handle data would cause power and knowledge to continue to be concentrated in a few hands, to blatantly hide the corruption and inequality that hit us as a society.

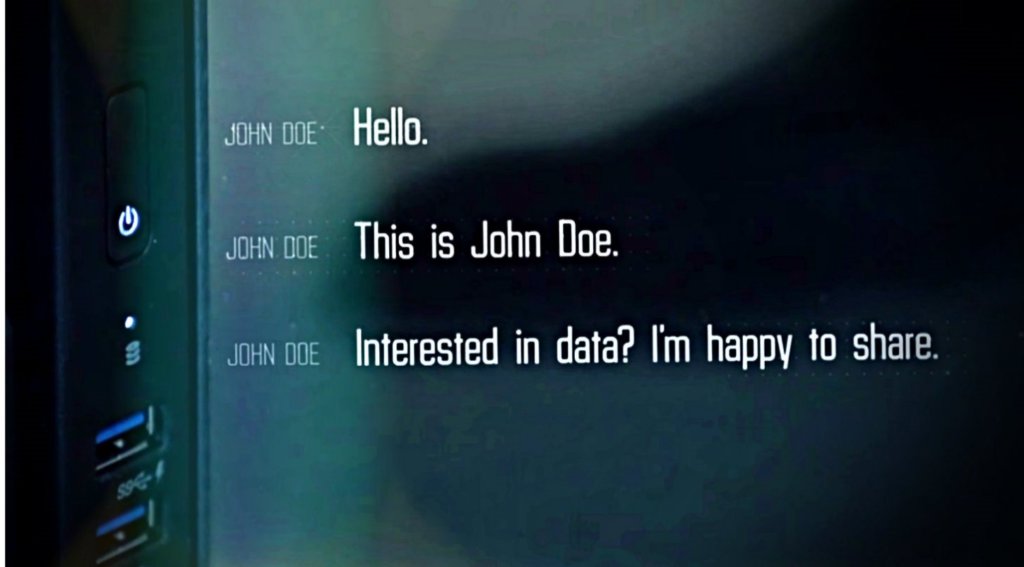

The magnitude of these implications was understood by two German journalists who, in 2015, received this message:

What would happen if you received an information and scoop offer like this one? What would happen today if you had access to a database that hides something important that must be journalistically disclosed? Are you ready to take on the challenge? Would you know how to face it, how to investigate it, and extract the knowledge you need from it?

These two German journalists did know how to do it. They knew how to manage and analyze databases. They had done it in the past.

But even so, given the dimension of what data revealed, they decided to share it with a team from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). The rest is history and you all know it: I’m talking about the Panama Papers.

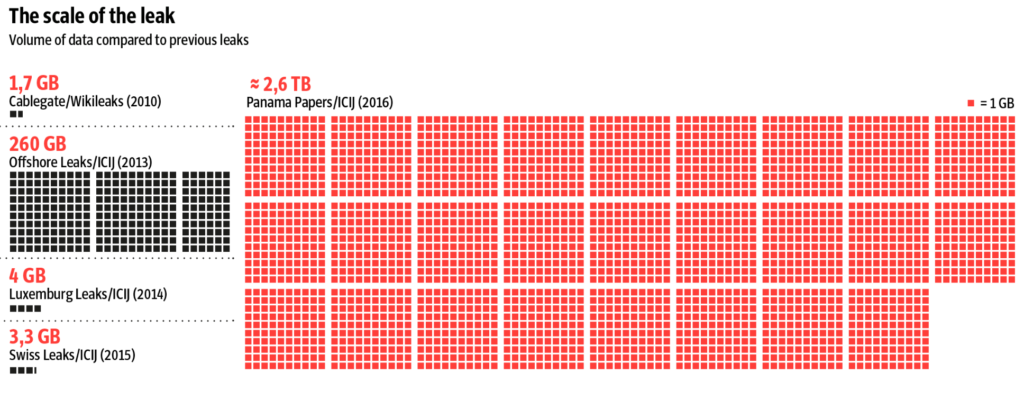

I´m showing this slide just for you to have an idea of the amount of data structured by the ICIJ team of engineers to make it digestible and easier for journalists to use it as an input in this global project.

It is an impressive amount of data, without a doubt, but, although it is one of the most irrefutable examples of the power that databases and algorithms give to journalism, it does not define, exclusively, what we know as journalism based on data analysis.

This journalism is not found only in terms of massive data analysis. As I wrote at the beginning, what massive data is or is not is relative, especially in Journalism.

To prove this, it is enough to see the different volumes of data that ICIJ has managed for previous projects with a global impact.

The volume of data is not the only extraordinary thing in an investigation. The surprising thing is what the journalist is able to reveal through the analysis of a database, regardless if it has hundreds or millions of records. What matters is the impact that the analysis has on society.

It is therefore crucial that the journalist have the knowledge to analyze databases, regardless of their size. The worst thing that can happen to a reporter is to freeze, contemplating a database with their arms crossed because, simply, they do not know how to process it – even in a spreadsheet.

Databases as a journalistic input

At this point, I want to give you a couple of examples of how, within the Data Unit of La Nación Costa Rica, we use data. I repeat, we focus more on the impact than on the volume of data.

This image is part of a news application that we developed for the municipal elections of February 2016. 81 mayors were elected and 605 candidates participated. We investigated them all and told the voters who they were.

How did we do it?

For five months, a team of five journalists took on the task of collecting or requesting all public information available on the 605 candidates.

We compiled the candidacies certificates of the Supreme Court of Elections, the criminal record and the sanctions or disqualifications to exercise public office of the Comptroller General of the Republic. Also, the amounts of debts the candidates had with the social security, both personal and their companies, all this, without leaving out their curriculum and political and community experience.

Most of the data collected came in PDF and Word; lots of information came also in paper files, other was collected through interviews, and the less came in Excel sheets.

All this data was systematized and structured in six databases and the information in those databases was subjected to exhaustive verification. That is an angular principle of Journalism and Data Journalism is no exception.

Numbers should never be taken as absolute truth, if we don´t check them thoroughly, they can induce us to blunder.

Next, we made the analysis: the interviews to extract the conclusions that allowed us to consolidate the evidence for each one of the investigations that we presented. We went out to the street, interviewed the protagonists of those stories, and wrote.

But analyzing data, investigating, and writing is just part of the job. Parallel to the foregoing, other processes were taking place.

Those six databases that we built for the project automatically went to the engineering data warehouse of the section. There, the process of data relationship and creation of algorithms for these databases took place for these to automatically feed the information that would contain the interactive news application.

What did the engineer in that warehouse do?

Relate all the information of those six bases by means of key fields. What is a key field? It is a unique number that was assigned to each candidate; in this case it was their personal ID number. This number was present in all the databases that we made and so we were certain that all the information attributed to each candidate was correct.

The six databases were obviously modified and edited along the process. The engineer created a solution for those changes to be incorporated in real time into his data management system. In this way, we avoided making mistakes of attributing crimes or sanctions to people that we later corroborated did not commit them.

Another algorithm for this project was the one that allowed the automated extraction, in real time, of the amounts owed by the candidates for social security, both personal and their companies. For this, a small robot went to the Social Security website and automatically consulted the candidate’s ID numbers or company number. The results were stored in a document with txt format, which was then converted into a spreadsheet. Here there was no possibility of error, if someone had not paid minutes before publishing our investigation, it would appear as in default; period.

All that information was automatically converted and updated in hundreds of html and Json documents (a light format for data description that is read by any programming language). This fed data to the application and guaranteed that the data load was not slow.

All this information came to the hands of the interactive designers and programmers, who were designing the user experience of the application and generating the interactive graphics that would accompany the conclusions of the data analysis that would sustain our reports.

The printed design and social media distribution area of La Nación was nurtured from this interactive part.

The final result was the news application and this series of publications based on the data collected and analyzed.

In this case, the databases were the entire Circulatory System of an investigation. Everything revolved around them. However, in journalistic projects it is not always this way.

Sometimes, databases are just one more artery that carries blood to oxygenate the investigation. Sometimes, the heart of an investigation is more likely to lie in a traditional method, but enriched and strengthened by databases, which we seek or create, to amplify the revelations we will make.

In August 2016, we published in the newspaper an investigation that showed how millions in public resources to educate the cooperative sector feed the businesses of private companies from what is supposed to be the center that should be in charge of training the sector.

We also showed that, in three decades, no one in the Government has supervised how part of that money is used.

To reach these conclusions in a conclusive way, we had to resort to more traditional methods of investigation: diving into more than 7,000 folios of documents that allowed us to reconstruct a good part of the history and decisions of this cooperative.

But we decided that the chronology of facts and evidence would be done in the form of databases, with evidence numbers, file number, identification of document photos, etc.

This method allowed us to relate information, facilitated the writing and verification of evidence to protect the investigation. The impact was great for a week. An investigation was opened in Congress, and it was ordered to stop the money transfers to the cooperative, among other reactions.

To complement the findings, we built and analyzed two databases that proved the existence of the other businesses that the questioned center has with the Government and how the National Liberation Party, the main proponent of laws and resources in favor of that Center, also nourished it through the political debt.

The investigation was called Cooperative Business, which can be consulted here.

For examples like the ones I just presented is that I like to define Data Journalism as:

Investigate a topic of public interest based on the analysis of databases, regardless if they contain millions, thousands or dozens of records. The publication may include data visualizations, news, and multimedia applications.

I´m often asked what it takes to be a journalist based on data analysis. Basically, a vocation to fulfill seven objectives:

- Be clear about your mission to protect a real public interest.

- Have an aptitude to investigate. Prove and expose facts that are deliberately hidden by someone in a position of power.

- Learn to analyze databases.

- Learn to solve problems, understanding that many times the solution is not given by a computer but by a mixture of techniques, statistical knowledge or basic mathematics, but above all a lot of journalist instinct.

- Understand how the logic of computing engineering and programming works to explain a problem and how to visualize a potential solution.

- Understand how a designer’s brain works; a journalist must have a clear idea of what they want to communicate with data.

- Teamwork. In data journalism, no journalist is an island. Even if you think you are alone in this, you will have to seek help from someone to solve a problem.

In that sense, journalism ceased to be long ago a thing of journalists alone. In the team I work in Costa Rica, there are journalists who choose to specialize in Economics, Business Intelligence, Data Mining and Statistics. There is a designer who started designing with a pencil and paper and then learned how to program. Finally, a computer engineer who is not only capable of managing databases, but also of programming (front end).

Throughout this article, I have spoken of the omnipresence of data in almost everything we do today; of the uses that we are giving it as humanity, and of the responsibility that we, as journalists, have to use it as another source to reveal what should be denounced in society.

I close with a quote from a writer of Science Fiction that is not a fiction:

«I think that technologies are morally neutral until we apply them. It is only when we use them for good or evil that they become good or bad, «William Gibson, writer.

Which side do you want to be on?