How are databases useful for journalism?, those numbers that sometimes seem so esoteric or infallible.

To answer, I want to tell you a story of a teacher, the principal of a high school located in a neighborhood of Limón, in the Costa Rican Caribbean zone.

Her name is Patricia Pinnock, and I scared her when we met two years ago. I came by surprise to her office and she imagined the worst when I said: I´m a journalist.

How would I not startle her! In the past, her school, the “Diurno de Pacuare”, had staged news for violence, drugs, robberies and, to top it off, a gang set fire to its facilities.

But I was not there for those reasons.

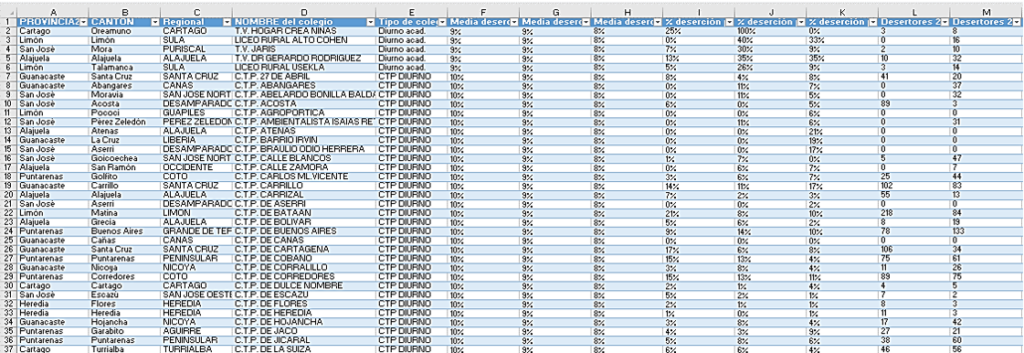

I opened my computer and said: look, I came because I analyzed a student desertion database with information from each school in Costa Rica and none of them reduced the student’s dropout as much as the one you represent. I want you to tell me how you did it.

Patricia looked at that mass of numbers and variables of 643 schools with dropout data between 2011 and 2013.

As disbelief persisted, we both reviewed the enrollment forms. In fact, in that school, the yearly dropout average was not 80 students, but 20.

Patricia’s eyes lit up, she started to laugh and we left her office.

What did I see? The corridors were clean, the walls full of color and murals, the classrooms were lit, and the furniture was in good condition. In the background, on a multi-purpose court, a basketball team was practicing.

How was that school, destroyed by the crime and violence from which all students had run away in 2009, reinvented into this new center?

When Patricia took over the direction of the Pacuare High School, one year after the vandalism acts, no local parent wanted to enroll their children there, the violence of the past frightened them.

So, the principal and her teachers knocked on every door in the neighborhood where a teenager lived. What would make them return and persist in their studies? Security, scholarships, food, a basketball team, a cricket team, a musical band with new instruments, a festival of the arts.

Immediately, teachers, parents and students began to work to make it happen. Their actions had a positive effect on lowering dropout rates.

Before interviewing the protagonist of this story, what I had in the database was only figures telling me that dropout rates at the Pacuare High School had fallen 25 percentage points between 2011 and 2013.

That was true, but it was just an acceptable title for desktop journalism.

It is clear that what was worth telling was not just the statistics, but the experiences of the students and teachers whose actions gave meaning to the data. The story of the Pacuare High School replicated in seven other schools we visited and according to the data, they were winning the fight against desertion.

How are databases useful for journalism?

- To find and narrate a story. Nonetheless, not the first story that crosses our path, but the best, the most faithful to the reality behind facts.

- To not settle for writing about general statistics, in which the experience of those behind the numbers and give meaning to them, gets lost.

- To create tools, such as applications or visualizations, that allow users to interact with data and find and create their own story, that of their most intimate interest.

- To not present to our readers certain facts analyzed by sources we sometimes call experts as true, in a false attempt to give depth to our notes.

- In addition to these new ways of narrating and serving the audience, databases also serve to investigate, to bring to light what others want to hide.

Believe me, not a few risk hiding improper acts amidst numbers and formulas, using the historical fear that journalists have expressed to anything that smells of mathematics.

Let me tell you another story. In my country, whenever we would go to the gas station to buy fuel, we would pay extra money for every liter of gasoline or diesel.

We did not know about that extra charge, much less that it was used for industrialists and entrepreneurs who repaired the streets to pay less for their liquefied petroleum gas and asphalt.

For eight years we helped subsidize $ 89 million.

How was the existence of this subsidy discovered? For a suspicion that my colleague Mercedes Agüero and myself had that something did not fit in the fuel prices formula.

We became obsessed with understanding the logic of the formula, took the scalpel and dissected its parts, with the help of the manual creation of a database.

The information was taken from 59 price fixing documents. That database was vital to prove the existence of the harmful subsidy.

But this was not all, along with its creation an exhaustive documentary research was carried out to find those responsible and the way they hid the math maneuver.

Thus, the clues took us to the then Regulator of Public Services, who modified the price formula in 2008.

The regulator denied the existence of the subsidy, but we had evidence of the database, documents, and the statement of one of the tariff analysts accepting that they acted under his orders.

One year after these revelations, the formula for fuel prices was modified.

For this purpose, databases are also useful in Journalism, as a compass to direct an investigation with impact.

Personally, I care more about impact than the volume of data I use to work everyday. That subsidy base, for instance, included less than 800 records.

We cannot DEFINE data journalism in terms of mass data analysis alone. The volume of data is not crucial. What is crucial is the precise conclusions that can be drawn from a database, regardless if it has hundreds or billions of records.

Speaking of definitions, we must not forget that journalists are not focused on research, database analysis, economics, environment or technical writing. Journalists are, in essence, focused on service to others, as Tomás Eloy Martínez would say.

You may wonder why, in addition to this example of the fuel subsidy, I chose a positive story like that of desertion? Why choose it instead of another investigation in which we reveal corruption?

Where is the “blood” in this report? one of my bosses would tell me.

That has been one of our weaknesses; believing that we should only tell how bad or negative things are.

The positive can also and must be shared. It should not be trivialized or reduced to corniness; we cannot ignore that the stories of people and the facts surrounding them are full of contrasts that must be narrated and proven.

Let us expose the corrupt without mercy, but if we find a story of someone overcoming all odds or ardently fighting against the system, let us expose it with the same passion and depth.

Just as we exalted the dedication of the teachers at the Pacuare region, we also denounced that staying at school is not enough, we also need quality education. We unmasked those who failed to control the students’ desertion and the flaws of the system that encourage it.

In journalism, there are no light topics, but reporters with light approaches. Our failure is to prejudge and label the topics.

In that sense, another weakness occurs when we reduce investigation to crime and political corruption and remove from the hard agenda the consequences of social inequality, or health or education public policies, among other issues that affect people´s lives.

Investigating the immediate consequence of a problem is valid, but most important is getting to the true background cause.

However, using databases and technology is not a guarantee of good journalism, both are a means, not an end in themselves.

They are tools that demand a great deal of precision and responsibility from the journalist who uses them, tools that work like a map of the treasure, guiding us to the place where the best stories, protagonists, and clues are.

But we cannot think that data analysis is enough to publish. We cannot forget that our task will always be to do JOURNALISM, go to the sites and sources to confront numbers with reality.

Journalism continues and will continue to be a matter of spending saliva, neurons, and soles of shoes; there lies the holy grail of the quality that we are looking for these days.